AI Coding Assistants Hamper Junior Developers’ Mastery of New Library, Study Shows

Updated (3 articles)

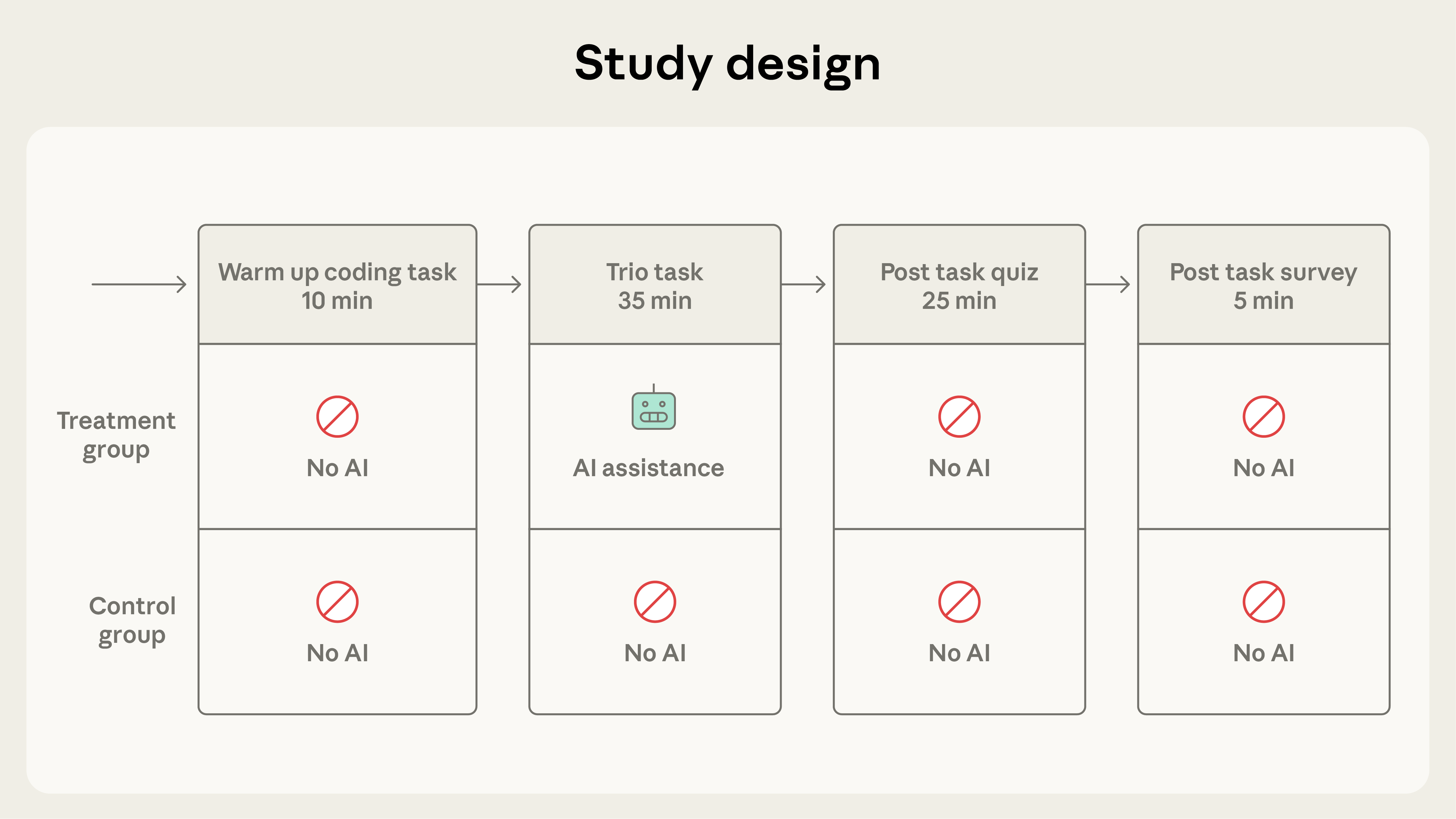

Randomized Trial Compared AI Assistance to Hand Coding The researchers recruited 52 junior software engineers who used Python weekly but had never worked with the Trio asynchronous library. Participants were randomly assigned to an AI‑assisted group using Claude.ai or a hand‑coding control group for a warm‑up task, two coding assignments, and a post‑task quiz [1]. The trial measured quiz performance, task completion time, and interaction patterns through screen recordings [1].

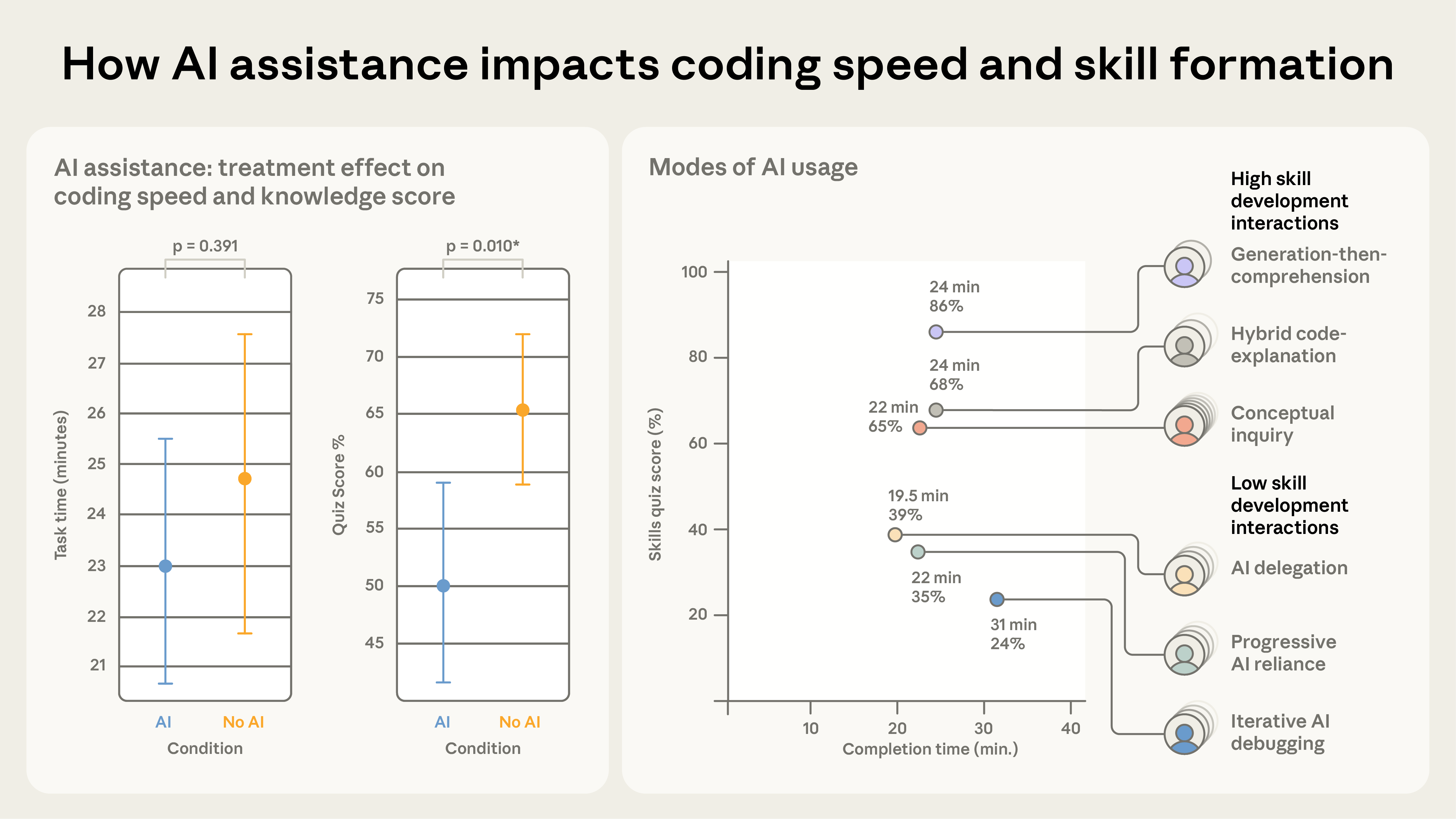

AI Users Scored Significantly Lower on Knowledge Quiz The AI‑assisted participants achieved an average quiz score of 50 %, compared with 67 % for the control group, a gap statistically significant (Cohen’s d = 0.738, p = 0.01) and equivalent to nearly two letter grades [1]. This 17 % deficit persisted despite participants completing the coding tasks with AI support [1]. The result suggests that reliance on AI for learning new concepts can impair knowledge acquisition [1].

Time Savings Were Small and Statistically Insignificant The AI group finished the coding tasks about two minutes faster on average, but the difference did not reach statistical significance [1]. Participants spent up to 30 % of session time formulating queries, with some users issuing as many as 15 prompts [1]. Consequently, the modest speed advantage did not offset the observed learning loss [1].

User Interaction Styles Determined Learning Outcomes Analysis identified low‑scoring patterns—AI delegation, progressive reliance, and iterative AI debugging—producing quiz scores below 40 %, while high‑scoring patterns—generation‑then‑comprehension, hybrid code‑explanation, and conceptual inquiry—yielded scores of 65 % or higher [1]. Interaction style, rather than mere AI usage, strongly correlated with mastery outcomes [1]. The findings highlight the importance of how developers engage with AI tools during learning [1].

Productivity Gains May Trade Off With Skill Growth Earlier observational work reported AI can cut task time by up to 80 %, yet this controlled study shows that such productivity gains may come at the cost of reduced skill development when learning unfamiliar libraries [1]. Researchers recommend designing AI modes that explicitly support learning, such as prompting conceptual inquiry rather than pure code generation [1]. Balancing efficiency with educational value will be crucial for future AI‑assisted development environments [1].

Timeline

Oct 2025 – An Oxford University Press survey of UK pupils finds six in ten say AI harms their schoolwork skills, while nine in ten report AI helps develop at least one skill and about a quarter feel AI makes work too easy, underscoring mixed perceptions and a demand for clearer usage guidance[1].

Dec 2025 – A MIT‑led EEG study of 54 participants shows AI‑generated essay assistance reduces activity in brain networks tied to cognitive processing and impairs participants’ ability to quote from their own essays, suggesting a possible decline in learning skills[1].

Dec 2025 – Carnegie Mellon University and Microsoft survey 319 white‑collar workers and discover that higher confidence in AI tools correlates with lower critical‑thinking effort on 900 AI‑handled tasks, warning of long‑term overreliance[1].

Dec 2025 – University College London professor Wayne Holmes warns that independent, scalable evidence on AI’s educational impact is lacking and urges substantial research into human‑AI interaction, user understanding of AI reasoning, and data handling[1].

Dec 2025 – OpenAI’s Jayna Devani tells the BBC that ChatGPT should serve as a tutoring aid rather than an outsourcing tool, advocating a “study‑mode” where students work with the AI to grasp difficulty and accelerate learning[1].

Dec 2025 – OpenAI secures a partnership with the University of Oxford, expanding the tool’s role in higher‑education collaborations and signaling growing institutional adoption of generative AI[1].

Dec 2025 – An AACSB survey reveals 85% of business‑school deans encourage AI use in classrooms, but only 63% of faculty agree, exposing a top‑down‑bottom‑up gap that hampers deeper integration of AI pedagogy[2].

Dec 2025 – A DEC poll finds 86% of students rely on AI for basic tasks such as information retrieval, grammar fixing, and drafting, while 58% feel unprepared for workplace AI demands, prompting calls to shift from tool use to co‑creation[2].

Dec 2025 – Queen Mary University of London pilots AI co‑creation in a business simulation and Nanyang Business School trains students to craft and critique GenAI prompts, illustrating emerging curricula that embed AI as a thinking partner rather than a coding substitute[2].

Dec 2025 – ESMT Berlin launches a custom AI platform with a personal learning mode and a course‑level assistant that identifies curricular overlaps and trains teaching assistants, exemplifying institutional investment in AI‑enhanced course design[2].

Jan 2026 – A randomized trial with 52 junior developers learning the Trio asynchronous library compares AI‑assisted coding (using Claude.ai) to hand‑coding and finds AI users score 17% lower on a post‑task quiz (50% vs 67%), a gap equivalent to nearly two letter grades[3].

Jan 2026 – The same trial shows AI users finish coding only about two minutes faster on average, a non‑significant speed gain that questions productivity benefits for novice learners tackling new concepts[3].

Jan 2026 – Interaction‑pattern analysis reveals low‑scoring learners rely on AI delegation and iterative debugging, while high‑scoring learners combine generation with comprehension and conceptual inquiry, highlighting the importance of how AI is employed for skill acquisition[3].

Jan 2026 – Screen‑recordings indicate participants spend up to 30% of session time formulating AI queries (≈11 minutes), explaining modest time savings and suggesting potential distraction from deep learning[3].

Jan 2026 – Researchers cite earlier observational work showing AI can cut task time by up to 80%, but this trial demonstrates a trade‑off where productivity gains may erode mastery, prompting a recommendation for intentional, learning‑focused AI modes[3].

All related articles (3 articles)

External resources (8 links)

- https://arxiv.org/abs/2601.20245 (cited 2 times)

- http://claude.ai/redirect/website.v1.db54c16f-a791-40de-aa29-5b838b946b42 (cited 1 times)

- https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.06590 (cited 1 times)

- https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.09089 (cited 1 times)

- https://code.claude.com/docs/en/output-styles (cited 1 times)

- https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9962584 (cited 1 times)

- https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4945566 (cited 1 times)

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-98385-2 (cited 1 times)